Discover compassionate dementia care strategies to nurture loved ones. Learn effective communication, practical tips, and caregiver support.

Navigating Dementia: A Guide to Managing Difficult Behaviors

Dementia Behavior Management: 4 Effective Tips

Introduction: Understanding Why Behaviors Change in Dementia

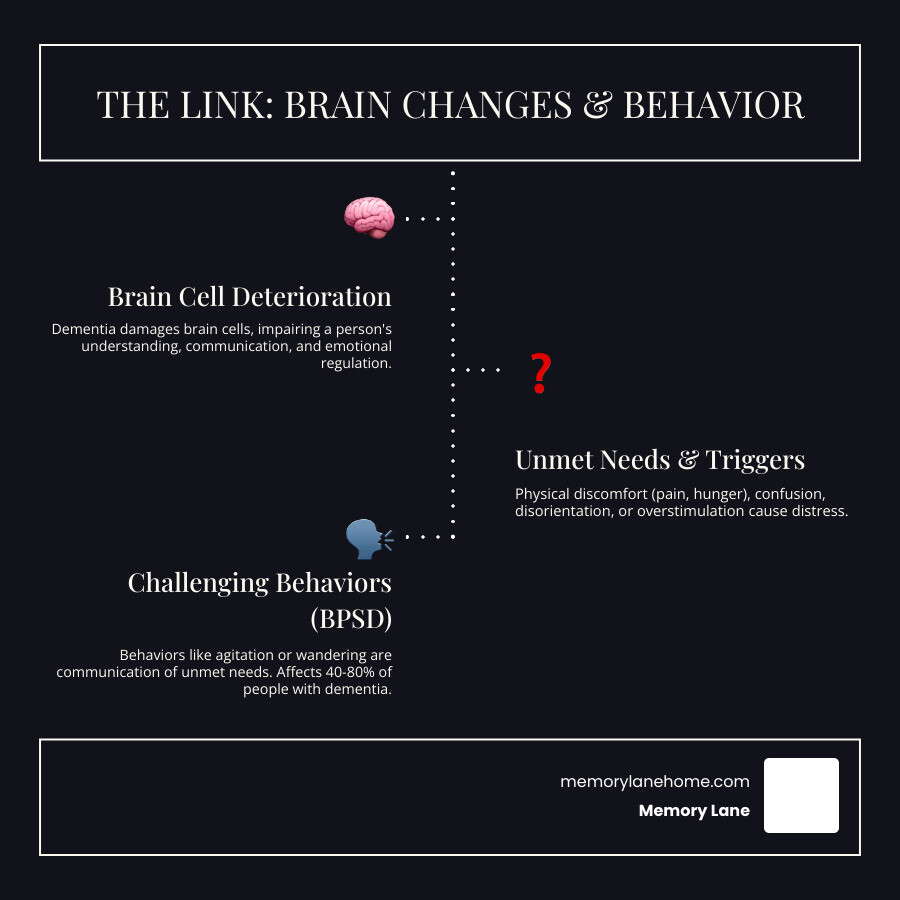

Dementia behavior management involves understanding that challenging behaviors—like agitation, wandering, or aggression—are often a person’s way of communicating unmet needs or distress. These behaviors affect between 40 and 80 percent of people with dementia and can be more distressing than memory loss itself.

Key Strategies for Managing Dementia Behaviors:

- Assess the situation – Use the ABC approach (Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence) to identify triggers

- Rule out medical causes – Check for pain, infections, constipation, or medication side effects

- Try non-drug approaches first – Create calm environments, maintain routines, and redirect attention

- Consider the Four Ds – Is the behavior Dangerous, Distressing, Disturbing relationships, or causing Disability?

- Support the caregiver – Prevent burnout through respite care and support groups

- Use medication cautiously – Only as a last resort when other strategies fail

When your loved one starts behaving in ways that seem out of character, it’s natural to feel overwhelmed and uncertain. Many people find these behavioral changes to be the most challenging aspect of dementia—even more difficult than memory loss. A person who was once gentle may become agitated. Someone who loved being social might wander away from home. These changes happen because dementia damages brain cells, affecting how a person understands their surroundings, communicates needs, and manages emotions.

The good news? Most challenging behaviors have underlying causes that can be addressed. Pain, confusion, overstimulation, or simply needing to use the bathroom can trigger distressing behaviors. By learning to see these behaviors as a form of communication rather than “problems to fix,” you can respond more effectively and compassionately.

The research is clear: non-pharmacological approaches—meaning strategies that don’t involve medication—should be your first line of defense. These include creating calm environments, establishing predictable routines, addressing physical discomfort, and learning to redirect attention. Medications carry significant risks and show only modest benefits at best, particularly for the behaviors families find most distressing.

As Jason Setsuda, a Board Certified Emergency Medicine Physician with experience in dementia behavior management through my work with Memory Lane Assisted Living and as a visiting physician specializing in elder care, I’ve seen how understanding the “why” behind behaviors transforms care outcomes. Our holistic approach to dementia behavior management emphasizes treating the whole person—mind, body, and spirit—not just symptoms.

A Systematic Approach to Dementia Behavior Management

Challenging behaviors in dementia signal that something is wrong. We must act like detectives to understand the underlying message. These behaviors are often unintentional responses to an altered perception of reality, an inability to articulate needs, or physical discomfort.

First, we consider the immediate triggers. Has there been a sudden change in environment, routine, or even the people around them? Moving to a new residence, a hospital admission, or even a change in caregiver can be incredibly disorienting and stressful for someone with dementia. We also evaluate if they are being asked to do something difficult, like bathing or remembering events, which can cause distress and frustration.

A crucial step in our systematic approach is a thorough medical evaluation. Sudden behavioral changes, especially if they are new or worsening, warrant a visit to the doctor. This is because many physical health problems can manifest as behavioral symptoms.

We use the ABC approach to systematically evaluate behavior. This involves:

- Antecedents: What happened immediately before the behavior occurred? What was the setting, time of day, who was present, and what activity was taking place?

- Behavior: A precise description of the behavior itself. What exactly did the person do or say?

- Consequence: What happened after the behavior? How did we, as caregivers, react?

By carefully tracking these elements, we can often identify patterns and triggers, giving us valuable insight into the “why.” For instance, if agitation consistently occurs before lunch, perhaps hunger is the antecedent. If it happens during bath time, maybe the water temperature or the perceived loss of control is the issue.

A critical part of this initial assessment is ruling out delirium. Delirium is a sudden, severe confusion or rapid change in mental function that can be caused by an underlying medical condition like an infection (such as a urinary tract infection or UTI), dehydration, pain, or medication side effects. Because delirium can present with behavioral disturbances that mimic worsening dementia, rule it out first. A doctor can assess for delirium and treat any reversible medical conditions.

We also look for unmet needs or environmental contributors. Is the person hungry, thirsty, or in need of using the restroom? Are they bored, lonely, or overstimulated? An environment that is too noisy, too dark, or too cluttered can increase confusion and agitation. Poor lighting, especially in the evening, can exacerbate sundowning.

Communication difficulties are another significant factor. As dementia progresses, individuals lose the ability to express their needs verbally. Therefore, their behavior becomes their primary form of communication. A person pacing back and forth might be trying to communicate a need to use the toilet. Someone pushing food away might have a delusion that it’s poisoned or be experiencing dental pain. Understanding this shifts our perspective from “problem behavior” to “communicative behavior.”

For a deeper dive into nonpharmacologic approaches, which we consider the cornerstone of our care, we often refer to comprehensive resources like “Managing Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia Using Nonpharmacologic Approaches: An Overview” from the National Institutes of Health. You can find more information here: Managing Behavioral Symptoms in Dementia Using Nonpharmacologic Approaches: An Overview.

Assessing the Behavior’s Impact with the ‘Four Ds’

Once we understand what is happening and why, we need to assess the behavior’s impact. We use the “Four Ds” framework to prioritize interventions and understand the risks associated with the behavior:

- Dangerous: Is the behavior dangerous to the individual with dementia or to others? This could include physical aggression, self-harm, or actions that put them at risk (e.g., wandering into traffic).

- Distressing: Is the behavior causing significant distress to the person with dementia, even if it’s not overtly dangerous? Or is it causing distress to caregivers or family members?

- Disturbing relationships: Is the behavior negatively impacting the person’s relationships with family, friends, or caregivers? This could involve verbal outbursts, paranoia, or social withdrawal.

- Disability: Is the behavior causing a functional disability, such as preventing them from eating adequately, leading to malnutrition, or causing frequent falls?

This framework helps us determine the urgency and intensity of our intervention. Behaviors that are dangerous or cause severe distress naturally take higher priority. Our goal is always to improve the safety, comfort, and quality of life for the individual while also supporting the well-being of their caregivers.

Investigating Physical and Medical Causes

As mentioned, physical discomfort or illness can be a significant driver of challenging behaviors. We always start by ruling out these reversible causes. It’s like a puzzle, and often, the missing piece is something treatable.

- Pain Assessment: People with dementia may not be able to articulate pain clearly. We look for non-verbal cues like grimacing, moaning, protecting a body part, or increased agitation. Untreated pain from conditions like arthritis, dental issues, or injuries can lead to restlessness or aggression.

- Infections (UTIs): Urinary tract infections are notorious for causing sudden confusion, agitation, and even hallucinations in older adults, especially those with dementia. We ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

- Constipation: A full bladder or constipation can cause immense discomfort, leading to restlessness, agitation, and even aggression. Regular bowel movements are crucial for comfort and behavior management.

- Medication Side Effects: We carefully review all medications, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements. Drug interactions or side effects can cause or worsen agitation, confusion, and other behavioral symptoms. Sometimes, simply adjusting a dose or timing can make a world of difference.

- Sensory Impairment (Vision, Hearing): Uncorrected vision or hearing problems can make the world a confusing and frightening place. People might misinterpret what they see or hear, leading to paranoia or agitation. Regular eye exams and hearing tests, along with ensuring proper use of glasses and hearing aids, are essential.

- Fatigue: Lack of adequate rest or sleep can dramatically impact mood and behavior. Exhaustion can lower a person’s tolerance for stimulation and increase irritability.

By systematically investigating and addressing these physical and medical causes, we can often alleviate or eliminate many challenging behaviors, improving the person’s overall well-being and reducing caregiver stress.

Non-Pharmacological Strategies: The Foundation of Care

At Memory Lane, we firmly believe that non-pharmacological strategies are the first and best line of defense in dementia behavior management. These approaches focus on understanding the individual, their environment, and their unmet needs, rather than simply suppressing symptoms.

Our approach centers on promoting both physical and emotional comfort. We create a calm and supportive environment, adapting routines and activities to the person’s abilities and preferences.

- Physical Comfort: This includes ensuring the person is not in pain, hungry, thirsty, too hot or too cold, or in need of toileting. We check for skin irritation, ill-fitting clothes, or anything that might cause physical unease.

- Emotional Comfort: We strive to create an atmosphere of security, familiarity, and reassurance. This means speaking in a calm, gentle tone, making eye contact, and offering a comforting touch. We avoid confrontation and arguments, as these only increase distress.

- Redirection Techniques: When a challenging behavior arises, redirection can be incredibly effective. Instead of arguing or correcting, we gently shift the person’s focus to a more pleasant or engaging activity. If someone is fixated on leaving, we might say, “Before we go, would you like to help me water the plants?”

- Creating a Calm Environment: We minimize noise, clutter, and overstimulation. Soft lighting, soothing music, and familiar objects can help create a sense of peace. We also ensure that the environment is safe, reducing risks for falls or accidents.

- Establishing Routines: Predictable daily routines for waking, meals, activities, and bedtime provide a sense of security and reduce anxiety. When a person knows what to expect, they feel more in control.

- Health Promotion Activities: Encouraging mental and physical activity is crucial. Daily walks, light exercises, or engaging hobbies adapted to their current abilities can improve mood, reduce restlessness, and promote better sleep. We also identify and treat cardiovascular risk factors, and educate about conditions like psychosis and depression.

For more detailed guidance on everyday care, we often recommend resources like “Tips for Everyday Care for People With Dementia” from the National Institute on Aging: Tips for Everyday Care for People With Dementia.

Managing Agitation, Aggression, and Sundowning

Agitation, aggression, and sundowning are among the most common and distressing behavioral symptoms. Agitation means a person is restless and worried, unable to settle down. Aggression can manifest as verbal outbursts or physical actions. Sundowning, a particular phenomenon, refers to increased restlessness, agitation, irritability, and confusion that occurs as daylight fades, typically in the late afternoon or evening.

Causes of agitation and aggression can be varied, including pain, depression, stress, lack of sleep, constipation, sudden changes in environment, feelings of loss, overstimulation, or being pressured to perform difficult tasks.

Our strategies for managing these include:

-

Coping with Agitation and De-escalation Techniques:

- Be patient and speak calmly: Your calm demeanor can be contagious.

- Listen without arguing: Acknowledge their feelings, even if their perception isn’t reality.

- Reassure the person: Let them know they are safe and you are there to help.

- Use non-verbal communication: Gentle touch (if appropriate), open body language.

- Distract and redirect: Offer a favorite snack, a familiar activity, or a change of scenery.

- Identify and remove triggers: If loud noises cause agitation, move to a quieter room.

-

Soothing Music: Music can have a profound calming effect. Playing their favorite tunes or gentle, familiar melodies can reduce anxiety and improve mood.

- Maintaining a Schedule: A consistent daily routine helps prevent confusion and anxiety, which are common triggers for agitation and sundowning.

- Light Exposure: Ensure plenty of natural light during the day, either outdoors or by a window. In the evening, use good lighting to prevent shadows and confusion, but avoid harsh, stimulating lights.

- Avoiding Caffeine and Alcohol: These substances can disrupt sleep patterns and increase agitation, especially later in the day.

- Discourage long naps late in the day: While naps can be beneficial, long naps close to bedtime can worsen nighttime sleep problems and sundowning.

For more comprehensive tips on managing these challenging behaviors, the National Institute on Aging provides excellent guidance: Coping With Agitation, Aggression, and Sundowning in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Practical dementia behavior management for wandering and rummaging

Wandering and rummaging are common behaviors in dementia that require careful dementia behavior management to ensure safety and maintain peace of mind.

-

Wandering Prevention:

- Identify the cause: Wandering often has a purpose, even if we don’t understand it. Is the person looking for something, trying to go “home” (even if they are home), or just restless?

- Create a safe environment: Secure all doors and windows with child-safety locks or alarms. Consider a “stop” sign on the door or a dark mat in front of it, which can act as a visual barrier.

- ID bracelets and Medical Alert Systems: Ensure the person wears an ID bracelet with contact information. Medical alert systems with GPS tracking can provide peace of mind and aid in locating a person if they do wander. Many local organizations, including those in Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and Saline, Michigan, can assist with these resources.

- Redirection and engagement: If the person is pacing or restless, redirect them to a purposeful activity or a short walk with supervision. Boredom can often fuel wandering.

-

Rummaging and Hiding:

- Understand the behavior: Rummaging can be a way to feel useful, search for something familiar, or simply a need to be active.

- Create a “rummage box” or “activity drawer”: Fill a designated drawer or box with safe, interesting items the person can sort through, such as old photos, fabric scraps, or familiar tools. This provides a safe outlet for the behavior.

- Secure valuables: Keep important documents, medications, and valuables locked away to prevent them from being misplaced or hidden.

- Distraction: When rummaging becomes disruptive, gently redirect the person to another activity.

LIST of safety tips to prevent wandering:

- Install child-safety devices on doors and windows.

- Hide items like coats, purses, or car keys that might prompt leaving.

- Use safety devices like bed alarms, chair alarms, or floor mats that alert you when the person gets up.

- Consider a medical alert system with location tracking capabilities.

- Notify trusted neighbors and local law enforcement about the person’s tendency to wander.

- Ensure the person wears an ID bracelet with current contact information.

- Keep a recent photo and an unwashed item of clothing (for search dogs) readily available.

- Check dangerous areas near the home (water, busy roads, balconies) frequently if the person is prone to wandering.

- If a person does wander, search within a one-mile radius, especially in the direction of their dominant hand, and investigate familiar places they might go.

Responding to Hallucinations, Paranoia, and Sleep/Eating Issues

These behaviors can be particularly unsettling for caregivers, but with the right approach, we can provide comfort and support.

-

Hallucinations and Paranoia:

- Validate feelings, avoid arguments: If your loved one sees something that isn’t there or believes someone is stealing from them, don’t argue with their reality. Instead, acknowledge their emotion. “I understand you’re scared,” or “It sounds like you’re worried about your belongings.”

- Reassurance: Offer comfort and a sense of security.

- Improve lighting: Shadows and poor lighting can exacerbate hallucinations. Use nightlights to reduce frightening visual distortions in the dark.

- Distraction: Gently redirect their attention to another activity or topic. Sometimes, moving to a different room can break the spell of a hallucination.

- Check for underlying causes: Infections, medication side effects, or sensory impairments can trigger these symptoms.

-

Managing Sleep Problems (including Sundowning):

- Consistent sleep schedule: Maintain regular bedtimes and wake times, even on weekends.

- Increase daytime physical activity: Regular exercise can promote better sleep.

- Optimize light exposure: Ensure exposure to natural light during the day and minimize bright lights in the evening.

- Limit naps: Discourage long or late afternoon naps.

- Avoid stimulants: Limit caffeine and alcohol, especially later in the day.

- Comfortable sleep environment: Ensure the bedroom is dark, quiet, and at a comfortable temperature.

- Bedside commode: Placing a commode near the bed can reduce nighttime wakefulness caused by needing the restroom.

- Soothing rituals: A warm bath, quiet reading, or gentle music before bed can signal it’s time to sleep.

-

Strategies for Eating Problems:

- Make mealtimes pleasant: Create a calm, distraction-free environment. Play soft music or use contrasting plate colors to make food more visible.

- Offer choices: Give limited choices (e.g., “Would you like soup or a sandwich?”) to maintain a sense of control.

- Adaptive foods: As chewing and swallowing difficulties arise, transition to softer foods, purees, or finger foods.

- Monitor medications: Some medications can affect appetite or cause dry mouth.

- Be patient and playful: Encourage eating with a positive, light-hearted approach. Small, frequent meals may be more successful than large ones.

Considering Medication: When and How to Use Pharmacological Treatments

While non-pharmacological strategies are always our first choice, there are times when pharmacological treatments may be considered for dementia behavior management. However, we approach medication with extreme caution and prioritize the safety and well-being of the individual.

- Last Resort: Medications are typically considered only when non-drug approaches have been thoroughly attempted and have failed, and the behaviors pose a significant danger to the person or others, or cause extreme, unmanageable distress.

- Risks vs. Benefits: It’s crucial to weigh the modest benefits of these medications against their serious risks. Many antipsychotic medications, for example, carry an FDA-mandated “black box” warning about an increased risk of death in older patients with dementia-related psychosis. They are also associated with increased risks of stroke.

- Antipsychotic Medications: These are often used off-label to treat agitation and aggression in dementia. However, the only atypical antipsychotic currently FDA-approved for agitation associated with dementia due to Alzheimer’s is Brexpiprazole (Rexulti®). We use these only under strict medical supervision, for the shortest possible duration, and at the lowest effective dose.

- Antidepressants and Anxiolytics: These may be considered for symptoms like depression or severe anxiety that are contributing to behavioral issues, again with careful monitoring.

Key principles for effective dementia behavior management

When medication is deemed necessary, we adhere to strict principles:

- Targeting Specific Symptoms: We aim to treat a specific, well-defined symptom (e.g., aggression, severe agitation) rather than general “behavior problems.”

- Start Low, Go Slow: Dosing is initiated at the lowest possible level and increased very slowly, especially for individuals sensitive to side effects.

- Regular Monitoring and Review: The person is closely monitored for effectiveness and any adverse side effects. Medications are reviewed regularly and tapered off if no longer needed or if risks outweigh benefits.

- Avoiding Restraints: We strongly advocate against the use of restraints—physical, chemical (using medication solely for sedation), or environmental (locking doors to restrict movement). Restraints can cause harm, reduce freedom, lead to loss of abilities, and often increase agitation. Our focus at Memory Lane is on creating a secure, engaging environment that eliminates the need for such measures.

The Caregiver’s Role: Ensuring Your Own Well-being

Caring for a loved one with dementia is an act of profound love, but it is also incredibly demanding. It’s easy to pour all your energy into their care and neglect your own needs, leading to caregiver burnout. We understand this challenge deeply, especially for family members in our Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and Saline, Michigan communities.

- Caregiver Burnout: This is a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion. Signs include irritation, social withdrawal, low mood, and exhaustion. Statistics show that between 40% and 70% of caregivers suffer from depression.

- Stress Management: Taking care of yourself is not selfish; it’s essential for both your well-being and your loved one’s quality of life. Regular exercise, a healthy diet, and sufficient sleep are fundamental.

- Seeking Help: Don’t hesitate to ask for help from family, friends, or local support services. This could be for practical tasks or simply for emotional support.

- Respite Care: Taking regular breaks, even short ones, is vital. Respite care services can provide temporary relief, allowing you to recharge.

- Support Groups: Connecting with other caregivers who understand your journey can be incredibly validating and provide a sense of community and practical advice. Many local organizations in Michigan offer these groups.

The National Institute on Aging offers excellent resources on this topic: Taking care of yourself as a caregiver.

Recognizing the Signs of Caregiver Stress

It’s important to be vigilant for the signs that you might be experiencing caregiver stress or burnout. These include:

- Irritation: Feeling easily annoyed or angry, even at minor things.

- Social withdrawal: Pulling away from friends and activities you once enjoyed.

- Anxiety: Constant worrying or feeling on edge.

- Depression: Persistent sadness, loss of interest, or feelings of hopelessness.

- Exhaustion: Chronic fatigue, even after rest.

If you recognize these signs in yourself, please reach out for support. You can find more information on recognizing caregiver stress and burnout here: signs of burnout.

Frequently Asked Questions about Dementia Behavior Management

What is the first thing I should do when a new challenging behavior appears?

First, rule out any immediate danger. Then, look for physical causes like pain, a urinary tract infection (UTI), constipation, or medication side effects. A prompt check-up with a doctor is crucial.

What is the ‘ABC’ method for understanding dementia behaviors?

The ABC method is a tool to understand triggers. A is for Antecedent (what happened before the behavior), B is for Behavior (the specific action), and C is for Consequence (what happened after). This helps identify patterns and potential causes.

Are medications always necessary for managing aggression in dementia?

No. Non-pharmacological strategies should always be the first line of defense. Medications are considered only when behaviors are severe, pose a danger, or cause significant distress, and other methods have not worked.

Conclusion: Creating a Path Forward with Compassion and Support

Navigating the behavioral changes that accompany dementia can feel like sailing uncharted waters. Yet, with understanding, patience, and the right strategies, we can create a calmer, more supportive environment for our loved ones. Behavior is communication—it’s their way of telling us something when words fail.

Our approach at Memory Lane, and the one we advocate for all caregivers, is rooted in person-centered care. This means seeing the individual beyond their diagnosis, understanding their unique history, preferences, and needs. It requires patience, creativity, and a willingness to adapt our responses.

Caregiver support is not just a nice-to-have; it’s vital. Taking care of yourself allows you to continue providing the compassionate care your loved one deserves. You are not alone on this journey.

For those seeking a supportive and safe environment, exploring professional dementia care services at Memory Lane can provide residents with personalized support and engaging activities, while offering families peace of mind. Our facilities in Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and Saline, Michigan, are designed with 24/7 personalized, compassionate support in mind, focusing on enhancing residents’ quality of life and independence through custom care plans and engaging activities. We are here to help you and your loved one find the best path forward.